Neurodiversity as Different Cognitive Operating Systems

Modern society is built on the assumption that people think, learn, and work in broadly similar ways. Education systems, workplaces, and social structures are largely designed around this assumption. Yet lived experience repeatedly shows that this is not the case.

One useful way to understand cognitive difference is to think in terms of different operating systems, rather than differences in intelligence or motivation.

This is not a medical model. It is a functional and explanatory one.

One Environment, Many Operating Systems

In technology, an operating system determines how information is processed, prioritised, and acted upon. A system designed for Windows will not automatically perform well when running software designed for Linux or macOS. The issue is not capability; it is compatibility.

In my opinion, human cognition works in a similar way.

People differ not only in what they can do, but in how they process information:

how they focus

how they learn

how they organise tasks

how they respond to stimulation

how they build understanding over time

These differences are often subtle, but they are fundamental.

Generalist Systems and Specialist Minds

Most modern systems are optimised for generalists.

They reward:

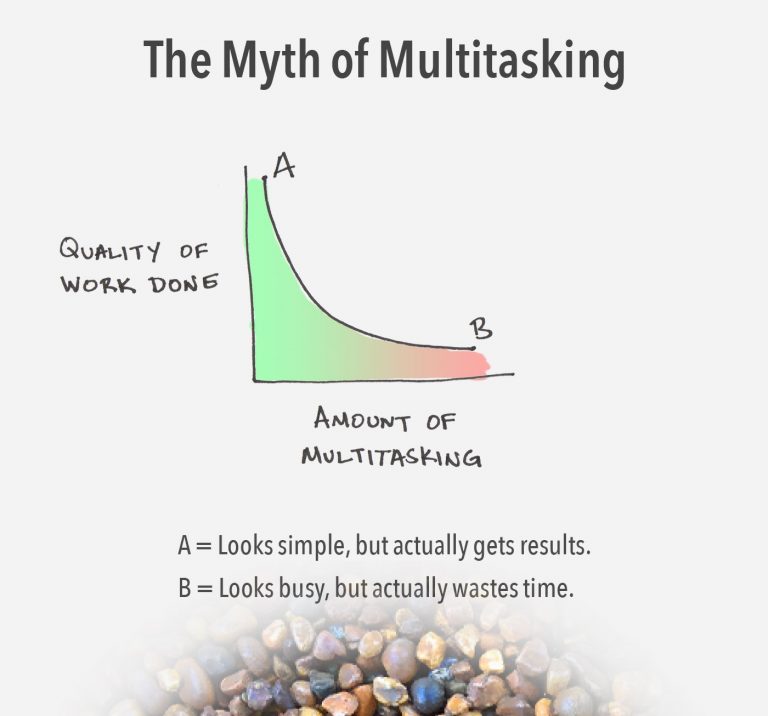

speed over depth

breadth over immersion

visibility over quiet competence

frequent switching over sustained focus

verbal fluency over internal modelling

These traits are not wrong. They are simply one configuration.

However, specialist cognitive profiles tend to operate differently. In many cases, they:

develop understanding through immersion rather than exposure

concentrate intensely on specific domains

build structured internal models before expressing conclusions

prioritise accuracy and coherence over speed

require the right conditions to demonstrate capability

When placed inside systems designed for generalists, these strengths often remain invisible.

When Mismatch Is Mistaken for Inability

A recurring problem is that system mismatch is often misinterpreted as lack of ability.

When someone does not respond well to:

rapid task switching

surface-level assessment

noisy or highly social environments

ambiguous expectations

constant performance signalling

the conclusion is frequently that they are disengaged, inconsistent, or underperforming.

In my view, this conclusion is usually incorrect.

What is being observed is not failure, but misalignment.

Why Misunderstanding Persists

Misunderstanding persists because most systems measure what they are designed to reward. They are very good at identifying strengths that match their own structure, and very poor at recognising strengths that develop differently.

This creates a feedback loop:

the system does not recognise the strength

the individual receives limited validation

confidence and opportunity narrow

capability is underutilised

Over time, this can shape identity, self-belief, and participation.

A Shift in Perspective

Reframing cognitive difference as operating system variation changes the question.

Instead of asking:

“Why doesn’t this person perform like others?”

We ask:

“What conditions allow this way of thinking to operate at its best?”

This shift does not lower standards. It improves alignment.

In my opinion, when environments are adjusted to recognise different cognitive operating systems, previously overlooked strengths often become clear: deep focus, precision, originality, systems thinking, and long-term problem-solving.

Towards More Compatible Systems

Understanding neurodiversity in this way encourages:

strength-first thinking

better environmental design

fairer assessment of capability

reduced misinterpretation of difference

It does not require labelling or diagnosis. It requires attention to how systems interact with people.

Closing Thought

Difference is not dysfunction.

Mismatch is not failure.

When systems are built with only one operating system in mind, they will inevitably overlook others. Recognising this is not a concession—it is a necessary step toward more inclusive, effective, and accurate ways of supporting human potential.