Reframing Difference: When Common Struggles Are Signs of Heightened Ability

Modern education and work environments are largely built around a narrow model of how attention, learning, communication, and productivity are expected to function. Within this model, behaviours that fall outside the norm are often described using deficit-based language: lack of focus, poor engagement, low resilience, or underperformance.

This framing is deeply ingrained. Yet it is also increasingly inadequate.

In practice, many commonly labelled “difficulties” are not indicators of weakness at all. They are often the visible side effects of heightened perception, intensified focus, or increased sensitivity operating within environments that are poorly aligned to those traits.

Beyond Deficit-Based Labels

Deficit-based labels attempt to explain difference by focusing on what appears to be missing. What they rarely examine is context.

In my opinion, this approach misunderstands how ability expresses itself across different cognitive styles. A person who struggles in one environment may function exceptionally well in another. The difference is not capability, but compatibility.

Heightened focus may present as disengagement when tasks lack depth or relevance. Increased sensory sensitivity may appear as avoidance in overstimulating settings. Strong pattern recognition may be misread as overthinking in systems that reward speed over structure.

These are not failures of ability. They are mismatches between individuals and the systems they are expected to operate within.

Perception, Focus, and Sensitivity as Strengths

Heightened perception allows for the detection of nuance, inconsistency, and detail that others may overlook. Deep focus enables sustained engagement with complex problems over extended periods. Sensitivity can support creativity, ethical awareness, and refined judgement.

However, these traits often require specific conditions to flourish. When environments prioritise constant interruption, rapid task-switching, or surface-level performance, such strengths can remain unseen or misunderstood.

The resulting narrative often centres on what an individual cannot do, rather than on what the environment fails to support.

A Systems Perspective on Ability

One useful way to understand this is through a systems lens. In technology, an operating system is neither good nor bad in isolation; its effectiveness depends on whether it is running compatible software.

In the same way, human ability does not exist independently of context. When systems are designed with only one mode of thinking in mind, those who operate differently are positioned as problems rather than contributors.

This perspective does not deny challenge. Instead, it relocates it. The question becomes not “What is wrong with this person?” but “What conditions allow this ability to function well?”

Moving Towards Strength-First Understanding

A strength-first approach does not romanticise difference, nor does it ignore areas where support may be needed. Rather, it begins with the assumption that ability is present, even when it is not immediately visible.

From this position, development becomes a process of alignment rather than correction. Environments, expectations, and measures of success can be adjusted to recognise diverse ways of thinking, focusing, and engaging.

In my view, this shift is essential—not only for individual wellbeing, but for innovation, resilience, and long-term societal capacity. Many of the capabilities most needed in a complex world are currently hidden in plain sight, mislabelled by systems that were never designed to recognise them.

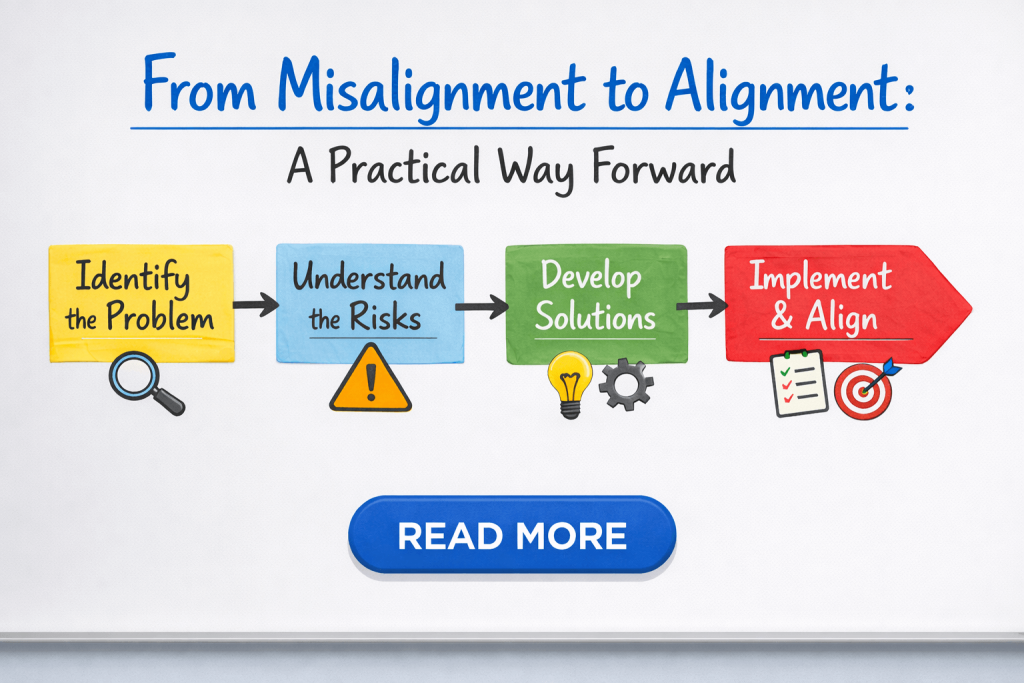

From Misalignment to Alignment: A Practical Way Forward

Recognising the problem is only the first step. The more important question is how individuals, families, educators, and organisations can respond constructively.

In my opinion, the solution does not lie in correcting individuals, but in improving alignment between people and the environments they operate within. This can be approached through a small number of practical stages.

First, shift the frame before changing the person.

Difficulty should be treated as a signal of misalignment rather than evidence of deficiency. This reframing alters decision-making, moving the focus away from compliance and towards understanding how attention and engagement naturally function.

Second, identify the conditions where strengths emerge.

Rather than concentrating on what does not work, attention should be given to when focus deepens, engagement improves, and performance stabilises. These conditions provide more useful guidance than generic performance measures.

Third, reduce friction before adding support.

Many challenges persist because environments introduce unnecessary obstacles. Small adjustments—such as reducing interruptions, increasing task depth, or allowing longer engagement cycles—often produce disproportionate improvements.

Fourth, build strength-first pathways gradually.

Alignment is achieved over time through iterative changes to expectations, structure, and feedback. Systems that offer multiple legitimate pathways allow strengths to surface without constant compensation.

Finally, treat alignment as an ongoing process.

As demands and contexts change, so too must environments. This is not a one-time intervention, but a way of thinking that informs future decisions.

Closing Reflection

Reframing common struggles as side effects of heightened ability invites a more accurate and humane understanding of difference. It challenges inherited assumptions and opens space for systems that recognise contribution beyond narrow norms.

The task ahead is not to reduce difference, but to understand it well enough to build environments where it can function as intended.